Sulu’s missions to China ultimately sought trade access and protection, using imperial recognition to secure commerce and deter rivals. Image Source: AI-generated

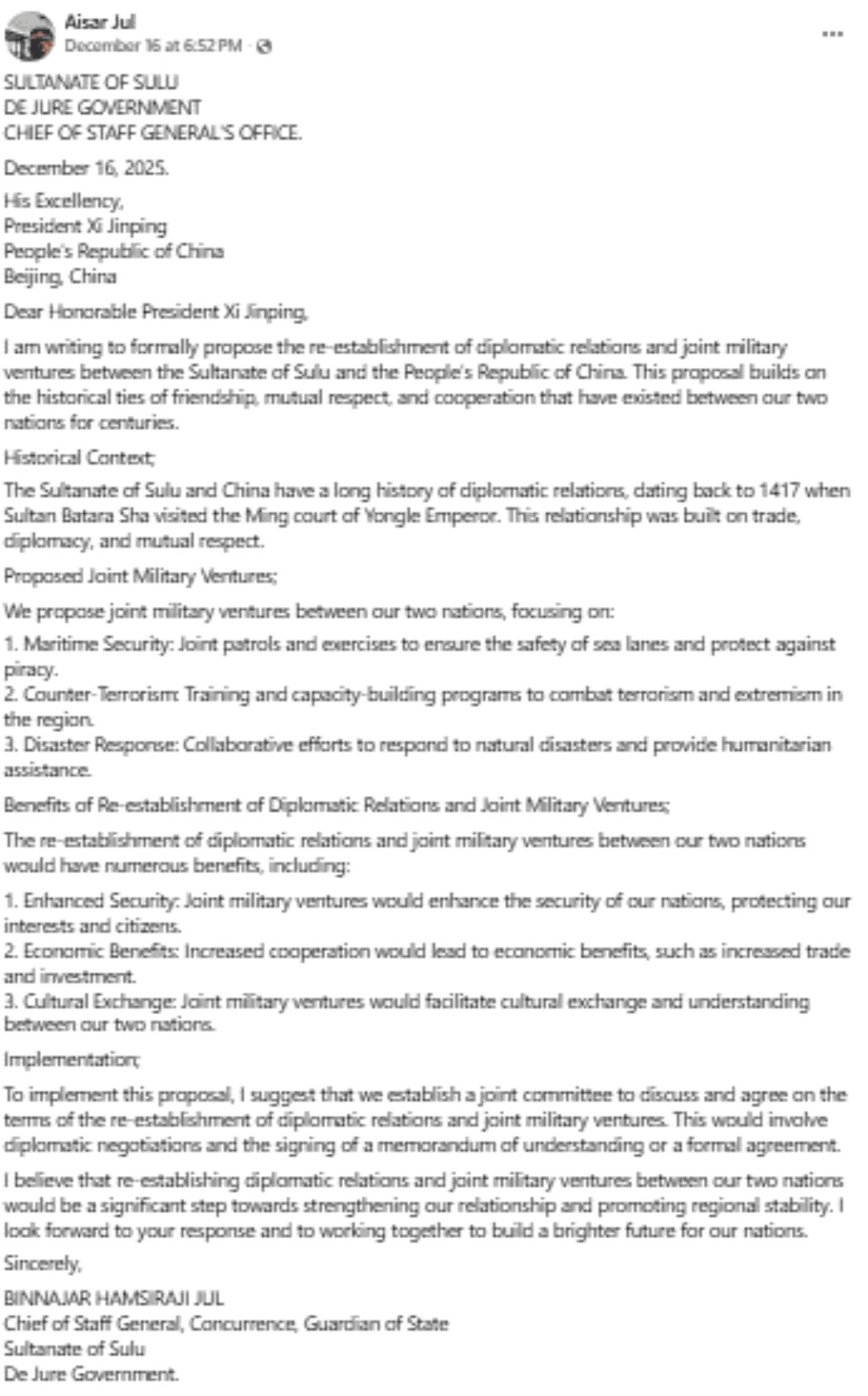

A letter circulating online, presented as official communication from a “Sultanate of Sulu De Jure Government” calls for diplomatic reset and joint military ventures with China.

Dated December 16, 2025, and addressed to President Xi Jinping, the document posted on Facebook frames its pitch as a return to centuries-old ties, invoking Sulu’s 15th-century missions to the Ming court. It then moves quickly from history to hard security: maritime patrols, counter-terror training, and disaster response cooperation, all under the banner of “re-establishing diplomatic relations” between “our two nations.”

The question for Mindanao, for Manila, and for Southeast Asia is not whether the letter reads like statecraft. It does. The question is whether the region should treat it as noise, provocation, or a signal, and whether, in today’s security climate, even “noise” can trigger consequences.

"There is also a deeper, recurring storyline here that Sulu has been forced to live through for years: every few years, a “new” Sulu Sultanate emerges, often with fresh titles, fresh letterheads, and fresh claims of sovereignty or international relevance."

There is also a deeper, recurring storyline here that Sulu has been forced to live through for years: every few years, a “new” Sulu Sultanate emerges, often with fresh titles, fresh letterheads, and fresh claims of sovereignty or international relevance. The public is asked to take each new iteration seriously. And when the cycle collapses, as it often does, the reputational and security cost lands on ordinary Sulu communities, not the people who authored the performance.

What the Letter Actually Proposes

The letter’s core offer is packaged in three pillars: maritime security joint patrols and exercises to “protect sea lanes” and deter piracy; counter-terrorism training and capacity-building to combat “terrorism and extremism”; and disaster response coordination and humanitarian assistance.

In isolation, those themes resemble the language of legitimate defense cooperation. But the source matters: Sulu is a province of the Philippines, and a self-declared “de jure government” has no lawful mandate to enter foreign relations. In Philippine constitutional design, treaties and international agreements are state functions routed through national institutions, and the Supreme Court has stressed, while upholding the Bangsamoro Organic Law, that BARMM is not a separate state, has no sovereignty, and does not have the power to enter into relations with other states; foreign policy and national defense remain with the national government.

There is also no public indication that Beijing has acknowledged the letter, and no indication that any official Philippine channel has been involved.

✉ Get the latest from KnowSulu

Updated headlines for free, straight to your inbox—no noise, just facts.

We collect your email only to send you updates. No third-party access. Ever. Your privacy matters. Read our Privacy Policy for full details.

Screenshot of Facebook post stating an official communication from a “Sultanate of Sulu De Jure Government. Posted by self proclaimed Chief of Staff General’s Office. Image Source: Facebook

Who Signed It, and What Can Responsibly be Said About Him

The letter is signed “Binnajar Hamsirahi Jul,” with the titles “Chief of Staff General, Concurrence, Guardian of State” of the purported “Sultanate of Sulu De Jure Government.” The Facebook post circulating appears under an account name that includes “Jul,” but the available screenshots do not establish that the poster and the signatory are the same individual, or that the identity presented is real.

A second graphic shared alongside the letter resembles an identification or appointment-style card. It repeats the name “Binnajar H. Jul” and includes additional names presented as approving officials, plus private biographical and contact details. Because those details include sensitive personal information, this report will not reproduce them.

What matters for public understanding is the verification problem: the identity behind the account that posted the letter is questionable and unverified. That does not prove deception, but it does mean readers should treat the claims as unconfirmed until independently corroborated.

"What matters for public understanding is the verification problem: the identity behind the account that posted the letter is questionable and unverified."

This is where Sulu’s repeating “new Sultanate” cycle becomes the core issue. Every few years, a new claimant structure appears, speaks in the voice of statehood, and demands to be treated as authority. The constant churn is itself destabilizing. It confuses who speaks for Sulu, invites outsiders to treat Sulu as perpetually contested, and repeatedly drags local identity into geopolitical narratives Sulu communities did not choose.

"It confuses who speaks for Sulu, invites outsiders to treat Sulu as perpetually contested, and repeatedly drags local identity into geopolitical narratives Sulu communities did not choose."

The implications split in two, and neither is good. If the account is real, it reflects reckless self-authorization, an individual presenting himself as sovereign and military authority in public, risking legal scrutiny and inviting security attention that can widen to communities. If the account is fake, it points to something more strategic: an attempt to plant an agenda on Sulu, to push people into arguments about sovereignty and allegiance, to make them question their past, present, and future political direction, and to bait reaction from the state and neighbors.

That possibility becomes sharper when you place this letter in the legal timeline of the wider “Sulu heirs” ecosystem, especially after the Paris Court of Appeal annulled the nearly US$15 billion arbitration award in early December 2025, a rupture that predictably increases incentives for “alternative measures,” new fronts, and new symbols.

Historical Context: The 15th-Century Sulu Missions to the Ming Court

The letter’s appeal to “centuries-old ties” deliberately echoes Sulu’s historic missions to the Ming court, long remembered for the diplomatic theater of tribute but, in practice, driven by trade access, prestige, and protection in a regional order that rewarded recognition.

That history is real. But invoking it today does not recreate sovereignty. It creates symbolism, symbolism that is easy to weaponize. The past becomes a costume for the present: “we had relations then,” therefore “we can restore relations now,” therefore “we are a nation.” That rhetorical bridge is emotionally powerful, and legally meaningless.

The Deeper Story: Sovereignty Language Without Sovereignty Constraints

The letter’s most revealing feature is how it borrows the grammar of statehood, “our two nations,” “re-establishment of diplomatic relations”, while operating outside the constraints recognized states must respect: constitutional authority, institutional accountability, diplomatic channels, and public oversight.

And here is where the revolving-door “new Sultanate” phenomenon becomes more than a local curiosity. It manufactures the appearance of sovereignty without responsibility. It turns social-media posts into quasi-state pronouncements. And it leaves the public, especially ordinary Sulu communities, to absorb the stigma and scrutiny that follow.

"If that earlier era was about selling fake titles, this new moment looks like an escalation: pushing toward fake nations that can “sign” fake treaties or at least produce documents that mimic them."

There is also a sharper comparison worth making. For years, Malaysian public discourse has warned about fabricated honorific-title economies, “Datukships” and similar awards marketed through dubious channels, including claims linked to self-styled royal figures. “Royal communiqué” style postings associated with the Royal Hashemite Sultanate branding also show the conferral of “Datuk/knighthood” titles as part of that performative ecosystem.

If that earlier era was about selling fake titles, this new moment looks like an escalation: pushing toward fake nations that can “sign” fake treaties or at least produce documents that mimic them.

Why This Matters Now: The Region is Primed to See Threats

In calmer times, a fringe “diplomatic” letter might be dismissed as theatrical politics. But the region is not calm, and governments are not reading ambiguous signals generously.

Major attacks and high-profile security shocks tend to recalibrate how states interpret online materials and non-state claims. In that environment, the risk is not that this letter proves capability. The risk is that it becomes usable, as a screenshot in a briefing, as a talking point in a border-security argument, or as “evidence” to justify tougher patrols and heavier scrutiny in an already sensitive corridor.

And if the identity behind the account is fake, the danger intensifies: the author can spark reaction while remaining unaccountable, letting Sulu absorb the blowback.

The Sabah Shadow: When “Sulu Claims” Become Counter-Terrorism Issues

The most direct regional parallel is Malaysia’s handling of Sulu-linked political actors tied to the Sabah dispute. Here, the line between symbolism and security has repeatedly blurred, especially when claim-making collides with territory, armed history, or international lobbying.

This is also why certain statements in the broader claim ecosystem raise alarms when “Sulu government” posts suddenly surface online. In November 2024, the New Straits Times reported lawyer Paul Cohen saying the heirs were “now free” to lease Sabah to other nations, explicitly naming China and the Philippines among possible lessees. Even if one treats that claim as rhetoric, it normalizes a dangerous idea: that Sabah can be traded geopolitically through private-law narratives and “sovereignty” performance.

When you combine that kind of talk, leasing Sabah to major powers, with a fresh social-media letter proposing “joint military ventures” with China, it becomes harder to dismiss these episodes as harmless local theater. They begin to look like an ecosystem of messaging designed to internationalize the dispute and keep new “authorities” appearing on cue.

Should surrounding countries treat this as a threat?

Not automatically. The letter does not prove an armed capability. It proves intent-signaling, rhetorical posturing, and a claim to authority not recognized by state institutions. On its own, that is not the same thing as a military threat. But ignoring it entirely would also be a mistake, because capability is only one part of the equation. The other part is how a message like this can be used.

As a diplomatic irritant, the document can be waved around to create the impression of an “invitation”, the idea that an outside power was asked to patrol, train, or “partner” in waters where sovereignty is politically sensitive. Even if no such partnership materializes, the claim alone can inflame distrust and complicate official diplomacy.

"As an information weapon, the letter is built for virality: the theater of titles, the symbolism of addressing China’s president, and the security keywords that travel fast."

As an information weapon, the letter is built for virality: the theater of titles, the symbolism of addressing China’s president, and the security keywords that travel fast. In a region primed to scan for cross-border threats, “joint military ventures” is language designed to trigger attention.

The more speculative, but increasingly relevant, question is motive. In January 2025, a Philippine column floated a strategy narrative in which “Sulu heirs” would pursue the claim in other venues and suggested that major-state endorsement, including China, could matter for pushing a petition through UN pathways. That claim should be handled carefully, because the ICJ’s contentious cases are for disputes between states, and the Court’s own statute is explicit that only states may be parties.

But precisely because only states can appear before the ICJ, any attempt to internationalize a contentious case would require a state sponsor to carry it. That makes the China-courting angle, still a stretch, at least conceptually intelligible as an information strategy: plant the idea that “China is being approached,” circulate an artifact that looks like diplomacy, then let others repeat it as if it were traction.

Is that proven by this letter? No. But in an ecosystem where “alternative measures” predictably intensify after a major Paris setback, the possibility cannot be dismissed outright as mere fantasy, because it doesn’t have to succeed to cause damage. It only has to circulate widely enough to muddy perceptions and provoke reaction.

"It only has to circulate widely enough to muddy perceptions and provoke reaction."

So should surrounding countries treat it as an imminent threat? Not on the evidence shown. But should they treat it as a security data point worth scrutinizing, precisely because it tries to internationalize a fraught space with the language of diplomacy and military partnership, and because it may be designed to seed larger political narratives? Yes.

What Should Happen Next?

This letter does not prove a military capability. It proves something else: an attempt to speak like a state, “two nations,” “diplomatic relations,” “joint military ventures”, from outside any recognized authority. In today’s security climate, that alone can be destabilizing.

After early December 2025, the Paris annulment marked a turning point that would predictably push claimant ecosystems toward alternative measures, new venues, new messaging, and, sometimes, the resurrection of symbolic institutions. In that context, the sudden emergence of yet another “de jure government” should be read less as diplomacy and more as part of Sulu’s recurring cycle: a new Sultanate-form claim, amplified online, asking the public to treat performance as sovereignty.

The signature matters because it signals what this is: self-authorization by an unverified identity, projected through the language of statehood. That is precisely why official institutions must respond with clarity and restraint, and why the public should refuse to grant automatic legitimacy to every new “Sulu Sultanate” that appears on schedule every few years.

In 2025, the most dangerous documents are not always those backed by tanks. Sometimes they are those backed by algorithms, released into a region already conditioned to expect the worst, and timed to exploit moments when alternative measures are being sought.

REFERENCES

Australian Broadcasting Corporation. (2025, December 17). Bondi shooter Naveed Akram charged by NSW Police over terrorist attack.

Australian Broadcasting Corporation. (2025, December 21). Remembering the 15 victims of the Bondi Beach attack.

Bernama. (2023, April 11). Malaysia Classifies Fuad A Kiram As A Terrorist.

International Court of Justice. (n.d.). Statute of the International Court of Justice (Article 34: Only states may be parties in cases before the Court).

Jul, A. (2025, December 16). [Facebook post].

KnowSulu (2025, May 19). How Fuad and Omar Kiram Sold a Nation That Wasn’t Theirs…

LawPhil. (2024, September 9). G.R. No. 242255 (full text).

Malaysia Sulu Case. (n.d.). About.

https://www.malaysia-sulucase.gov.my/

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Malaysia (Wisma Putra). (2025, December 10). Press Statement: The Paris Court of Appeal annuls the purported “Final Award” in the Sulu Case.

New Straits Times. (2024, November 11). ‘Heirs’ now free to lease Sabah to China, Philippines, says lawyer.

Reuters. (2025, December 10). French court annuls cash bid by late sultan’s heirs in Malaysia land dispute.

Reuters. (2025, December 21). Australia honours Bondi Beach attack victims; PM Albanese booed.

Senate Electoral Tribunal. (n.d.). 1987 Constitution.

Senate of the Philippines. (2018, July 27). Republic Act No. 11054: Organic Law for the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (PDF).

Supreme Court of the Philippines. (2024, September 9). SC Upholds Validity of Bangsamoro Organic Law; Declares Sulu not Part of Bangsamoro Region.

The Philippine Star. (2017, September 23). Commemorating 600 years of a royal voyage.

The Straits Times. (2023, April 11). Malaysia lists Sulu heir as a terrorist in claim over Sabah.

The Star (Malaysia). (2013, June 22). Datukships from ‘Sultan’ fake.

The Daily Tribune. (2025, January 27). Scuttlebutt 160.

The RHSSS Foreign Ministry (RHSSS News / WordPress). (2012, February 21). Royal communiqué: Royal Grant of Knighthood as Datuk / Knight of The Royal Order of Sulu & Sabah…