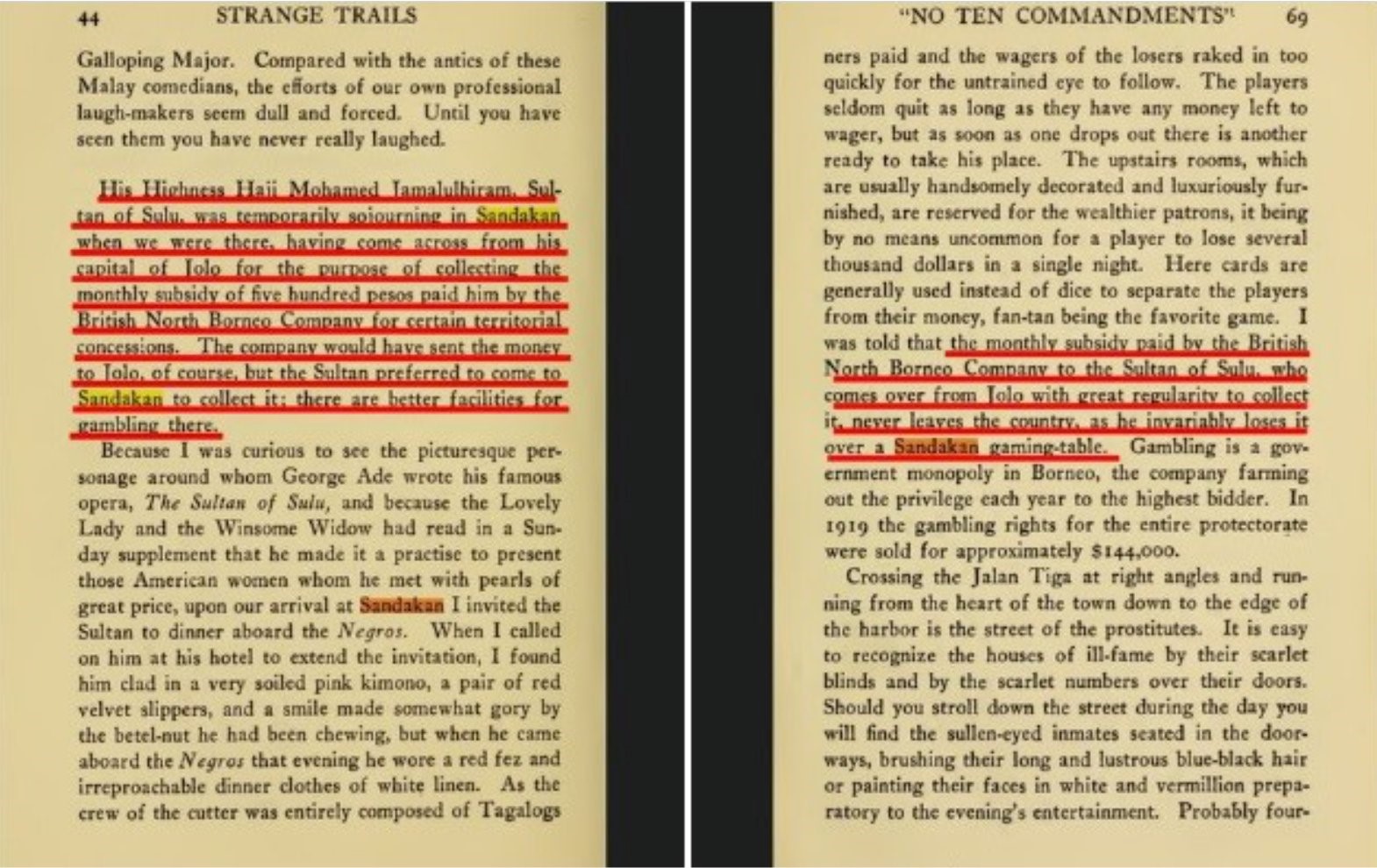

Sultan Jamalul Kiram II at a high-stakes gaming table, symbolizing his gambling debts and financial pressures that shaped his era. Source Image: fictional, original self-designed artwork created for this article

While the current legal circus surrounding the Sulu claim attempts to paint a picture of a lost "maritime kingdom" with a high, minded sovereign strategy, the historical reality is far more earthly, and far more desperate. To understand why the 1878 Agreement was signed, one must look past the legal footnotes and into the gambling dens of Singapore and Sandakan frequented by the last undisputed Sultan, Jamalul Kiram II.

Where the Strange Trails Go Down

A Contemporary Witness Edward Alexander Powell (1879–1957), author of many books including Fighting in Flanders (1914), The Last Frontier: The White Man’s War for Civilisation in Africa (1912), Gentlemen Rovers (1913) and Where the Strange Trails Go Down (1921), was not a mere travel enthusiast but one of America’s most prolific war correspondents and adventure writers of the early twentieth century. Having reported from the frontlines of World War I and served in U.S. military intelligence, Powell brought to his travelogues a sharp eye for political undercurrents and the human dramas behind imperial expansion. His 1921 book, which chronicled journeys through Malaysia, Borneo, Siam, Cambodia, and Cochin, China, was part reportage, part ethnography, and part adventure tale, written in a style that blended vivid description with a journalist’s instinct for uncovering uncomfortable truths.

Cover of the 1921 travelogue, Where the Strange Trails Go Down, by E. Alexander Powell

A Sovereign at the Gaming Table

In his 1921 travelogue, Where the Strange Trails Go Down, E. Alexander Powell provides a candid, non, legalistic view of Jamalul Kiram II. Far from the image of a secluded, austere monarch, the Sultan was a man of the world with a well, documented weakness for the finer things, and the gaming table. Powell describes a ruler who was frequently found in the cosmopolitan hubs of Southeast Asia, far from the daily governance of Jolo, engaging in high, stakes baccarat and poker.

Powell’s account strips away the romantic veneer of sovereignty and reveals a ruler entangled in the cosmopolitan vices of his age. By situating the Sultan not in the halls of power but at the baccarat tables of Singapore, Powell’s narrative underscores how personal indulgence and financial desperation shaped decisions that later acquired outsized geopolitical significance. His work thus provides a contemporaneous, non, legalistic lens: a reminder that the origins of the Sulu claim lie less in grand strategy than in the everyday debts and distractions of a monarch whose kingdom was already slipping through his fingers.

This penchant for gambling was not merely a private hobby; it was a primary driver of the Sultanate’s financial policy. History reveals that Jamalul Kiram II was a man perpetually in need of liquid capital to cover his losses. His lifestyle in Singapore, characterized by Western tailoring and expensive tastes, required a steady stream of cash that the internal revenues of a dwindling Sultanate could no longer provide.

✉ Get the latest from KnowSulu

Updated headlines for free, straight to your inbox—no noise, just facts.

We collect your email only to send you updates. No third-party access. Ever. Your privacy matters. Read our Privacy Policy for full details.

The 1878 Agreement: A Personal Bailout?

This historical context sheds a new, unflattering light on the 1878 Agreement, the very document at the heart of the current claims. While modern lawyers like Paul Cohen attempt to frame the agreement as a sophisticated international lease of territory, the Sultan’s contemporary reality suggests a much simpler motivation: the immediate need for a "pension" to satisfy creditors.

By agreeing to the annual payment of 5,000 (later 5,300) ringgits, Sultan Jamalul Alam wasn't securing the future of his people; he was most certainly securing his next hand at the table. The "sovereign state" that the claimants now speak of was, at the time, being bargained away piecemeal to fund a personal lifestyle that the Sultan could not afford. The 1878 act confirmed a dynamic where the "heirs and successors" were already being sidelined in favor of immediate cash flow for the reigning monarch.

From Baccarat to Billion Dollar Claims

The irony is stark. The current "Sulu Fantasy", bankrolled by financiers who treat litigation like a speculative investment, is based on the signatures of a man who would have likely been baffled by the modern valuation of his debts. Jamalul Kiram II died in 1936 without direct heirs, leaving a legacy of unpaid markers and a Sultanate of self-proclaimed successors who have replaced his gambling cards with legal subpoenas.

The true heirs of Sulu are the people who remained on the land, while the "royalty" sought fortunes abroad. By focusing on the historical reality of the "Gambling Sultan," we see the Sulu claim for what it truly is: not a struggle for indigenous justice, but a long, running commercial dispute rooted in the financial desperation of a man who bet his kingdom and lost.

Screenshots of pages 44 and 69 of the 1921 travelogue, Where the Strange Trails Go Down, by E. Alexander Powell

Doubling down

Modern Sulu claim litigation funders are, in effect, leveraging a 19th-century document like a distressed asset, pricing it not by what it meant on the ground in 1878, but by what it can be made to yield in courtrooms today. Read alongside Powell’s portrayal of Jamalul Kiram II, the agreement looks less like a masterstroke of statecraft and more like an urgent cashflow patch: a ruler trying to stay afloat in a world where his authority was shrinking and creditors were very real.

That’s where the “national destiny” framing becomes useful, not because it clarifies history, but because it conveniently disguises a commercial project. The claim’s modern architects have repeatedly treated the past as something to be re-cut for maximum advantage: turning contingency into sovereignty, sanding down inconvenient context, and presenting Sulu’s people as the moral wrapper for what is, at bottom, a high-value extraction play. The same instinct shows up in the legal strategy: when facts resist, the storyline flexes; when nuance complicates, it’s edited out. And you could see the reflex again after the Paris Court of Appeal annulled the purported Final Award on 9 December 2025: Paul Cohen’s public line “Malaysia… cannot change the sovereignty decisions that it has bought at such a price”, didn’t so much engage the ruling as pivot back to a sovereignty-infused narrative designed to keep the political aura intact while the commercial engine keeps running.

And the cost is engineered to fall on ordinary people on both sides of the border. Whatever grand language is used, the practical effect is to make Malaysia, and by extension ordinary Malaysians, especially those with no say in these maneuver’s, the counterparty to a bet they never placed; while ordinary Filipinos are sold a heroic narrative that doesn’t pay their bills or fix decades of neglect in Sulu.

In the end, it’s a scheme that asks two publics to carry the burden, through tension, distraction, and potential liability, so a small circle of claimants, lawyers, and funders can monetize a myth. Strip away the pageantry and the claim reads less like indigenous justice, and more like an old debt, repackaged, refinanced, and sold as a billion-dollar story at common Malaysian and Filipino expense.

REFERENCES

Powell, E. Alexander. (1921). Where the Strange Trails Go Down. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/

Paris Court of Appeal. (2025, December 9). Order of 09 December 2025, Case No. RG 22/04007. https://iamaeg.net/

KnowSulu. (2025, April 2). Profit Over Partnership: Exposing Therium’s Fine Print. https://knowsulu.ph/

KnowSulu. (2025, October). The Claim That Forgot Its People and the Real Cost of the Sulu Fantasy. https://knowsulu.ph/

International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). (2025, November 6). Nurhima Kiram Fornan and others v. Kingdom of Spain (ICSID Case No. ARB/24/45), Award (redacted). Italaw. https://www.italaw.com/

Reuters. (2025, December 10). French court annuls cash bid by late sultan’s heirs in Malaysia land dispute. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/