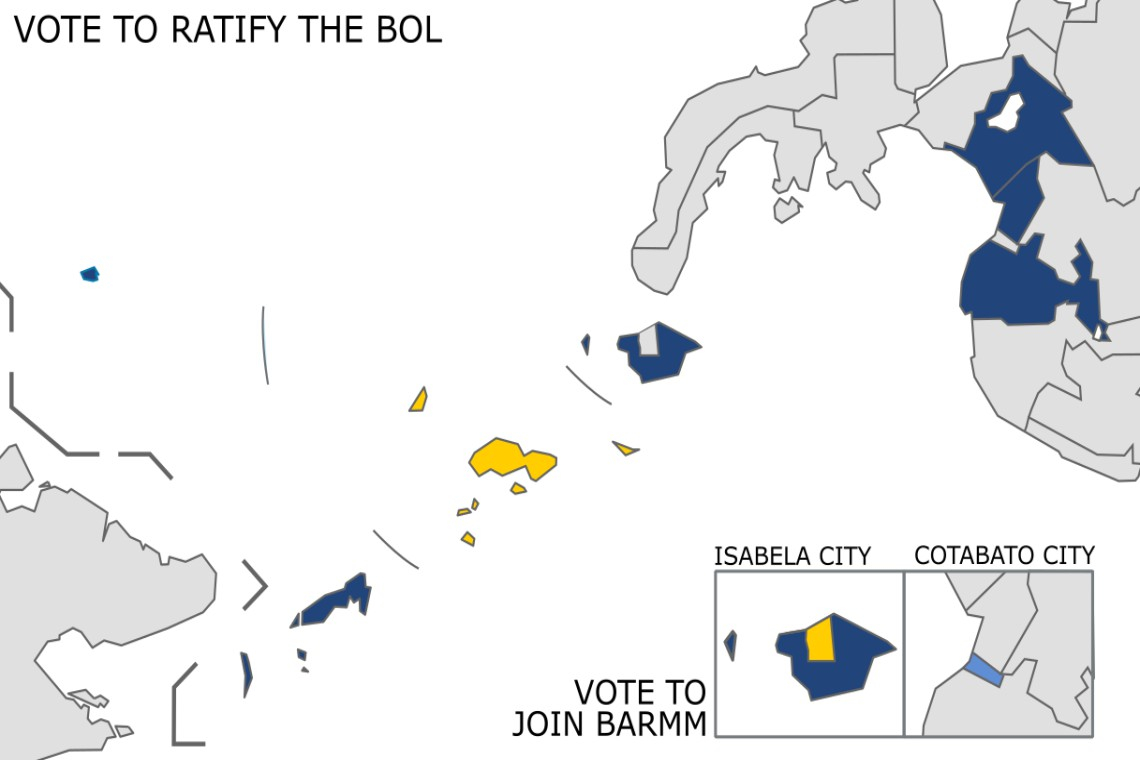

Results of the 2019 plebiscite on BARMM: Sulu voted “No” while the rest of the ARMM voted “Yes.” Years later, some in Sulu are reconsidering whether that decision served the province’s future. Image Source: 2019 Bangsamoro Autonomy Plebiscite (Wikiwand)

As BARMM prepares for its first parliamentary elections and secures international funding, Sulu finds itself politically excluded yet economically entangled—raising new questions about autonomy, representation, and regional identity.

When the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) was created in 2019, it was hailed as a historic turning point in the long and violent struggle for Moro self-determination. Born out of the 2014 Comprehensive Agreement between the Philippine government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), BARMM replaced the largely dysfunctional ARMM (Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao) with the promise of real autonomy: fiscal power, a functioning regional parliament, and greater control over ancestral land and resources. But today, as BARMM prepares for its first democratic elections this October, one of its founding provinces, Sulu, has been left behind.

This exclusion, however, is not the product of accident or neglect. It was Sulu that chose to leave—but not without contest. In the 2019 plebiscite that ratified the Bangsamoro Organic Law, Sulu voted against joining BARMM. Official results showed that 163,526 Sulu voters (54.3%) opposed inclusion, while 137,630 (45.7%) supported it. This opposition reflected the stance long held by many of the province’s political elites, particularly Governor Abdusakur Tan II, who consistently campaigned against integration into BARMM. Their resistance centered on both legal and identity concerns: they argued that the “ARMM-as-one” provision in the Organic Law, which treated all ARMM provinces as a bloc in the vote, violated Sulu’s locally expressed opposition to BARMM. Despite Sulu’s local majority voting “No,” it was swept into BARMM due to the aggregate ARMM-wide result.

What began as a political objection soon escalated into a legal confrontation. Tan and his allies brought the case before the Supreme Court, which—after years of deliberation—ruled in 2024 that Sulu’s inclusion was indeed unconstitutional. While the decision was hailed as a win for local autonomy, the aftermath exposed deeper structural challenges. The ruling severed Sulu from BARMM in legal terms but left no roadmap for governance, funding, or administrative continuity. As a result, the province now finds itself legally outside the Bangsamoro framework but with no substitute for the systems and resources that BARMM had begun to establish.

With the vote relatively close, and given the region’s current uncertainty, some local officials and community leaders are now reconsidering whether that resistance reflected the province’s long-term interests.

No Exit Strategy

This legal vacuum continues to have real consequences. With Sulu’s seven parliamentary seats removed, BARMM legislators are scrambling to reallocate representation. Proposed bills such as Parliament Bill 347 and 351 seek to distribute those seats among remaining provinces, but the rebalancing is creating tension, especially with elections approaching. The Commission on Elections (Comelec) has delayed ballot printing to account for seat redistribution, and the first parliamentary elections have been rescheduled to October 13, 2025. While BARMM moves forward, Sulu remains conspicuously absent. In May 2025, the Bangsamoro Parliament adopted Resolution 546, urging the Intergovernmental Relations Body (IGRB) to oversee Sulu’s administrative and fiscal transition and ensure uninterrupted public services in the province. Meanwhile, the Commission on Elections (Comelec) has decided to proceed with the election based on 73 seats, excluding Sulu’s seven seats, while awaiting final decisions on seat reallocation. These moves signal that although Sulu is no longer within the formal structure, governance actors are taking steps to manage its exit responsibly and avoid governance vacuums.

The timing is also complex for Sulu. BARMM has secured $400 million in blue economy funding from the Asian Development Bank, aimed at boosting marine livelihoods and coastal resilience. Although Sulu is no longer formally part of BARMM, Chief Minister Macacua has stated that the funding will still benefit the coastal provinces of Basilan, Tawi-Tawi, and Sulu. This means that Sulu is likely to receive support in areas such as seaweed farming, fisheries, and maritime infrastructure. However, its exclusion from the region's decision-making processes may still limit how effectively those resources are accessed or aligned with local priorities. Although some national lawmakers and local stakeholders have called for a plebiscite to reconsider reintegration, the Commission on Elections has ruled that such a vote is not feasible this year, citing time and procedural limitations. In some ways, the province now straddles a line between inclusion and marginalization.

The province now straddles a line between inclusion and marginalization.

On the ground in Sulu, reactions are mixed. While the political leadership heralded the Supreme Court decision as a restoration of local dignity, many Tausug residents express concern over deteriorating services and lost opportunities. "We were told we won, but what did we win?" said a community leader in Jolo.

✉ Get the latest from KnowSulu

Updated headlines for free, straight to your inbox—no noise, just facts.

We collect your email only to send you updates. No third-party access. Ever. Your privacy matters. Read our Privacy Policy for full details.

Power, Paramilitaries, and the Price of “Autonomy”

In response to this political limbo, the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), long rooted in Sulu and the broader Tausug identity, has called for Sulu to be reintegrated into BARMM. Their appeal to Congress emphasizes the disenfranchisement of Tausug voices and the need for unity among the Bangsamoro people. As MNLF central committee chairman Muslimin Sema asserted, “Sulu is an integral component of the collective aspiration of the Moro people in Southern Philippines for progress and peace via self‑governance.” The MNLF also criticized the Supreme Court’s decision, stating, “It is hurting for us to see Sulu taken out from the Bangsamoro region’s area of coverage.” The MNLF may also be leveraging this moment to reassert its relevance in a political landscape increasingly dominated by the MILF. As the MILF cements its leadership within BARMM's institutional framework—including control over parliamentary appointments and regional ministries—the MNLF risks being politically sidelined. By calling for Sulu’s reintegration, the MNLF not only positions itself as a defender of Tausug representation but also challenges MILF hegemony over the broader Bangsamoro narrative. In the absence of formal structures, MNLF-linked actors have been more visible locally, reviving calls for federalism, island autonomy, and, in some corners, revanchist claims to Sabah.

“It is hurting for us to see Sulu taken out from the Bangsamoro region’s area of coverage.”

This last point connects Sulu’s local aspirations to a larger geopolitical narrative. Some Sulu actors have long used the region’s historical claim to Sabah as a symbol of sovereignty and legitimacy. In this context, exiting BARMM could have been a strategic move to free the province from MILF-led constraints and to project an independent identity capable of pushing more forcefully for those claims. Yet, more than six years after the 2019 elections and six months after the Supreme Court decision, little has been done at the local level to build the institutions or coalitions necessary for such an agenda. Instead, with no access to BARMM funds and limited coordination with Manila, Sulu’s position may be weakening rather than strengthening.

The security implications are equally concerning. While BARMM has improved its coordination with the national government to combat violent extremism, particularly in mainland Mindanao, Sulu’s isolation could create enforcement gaps. Intelligence officers warn that Abu Sayyaf factions, which still operate in Sulu’s remote areas, may exploit administrative ambiguity or reduced funding to regroup. To help safeguard electoral credibility across the region, Sulu stakeholders are now included in the Independent Elections Monitoring Center (IEMC), a multi-stakeholder body made up of civil society groups such as IAG, NAMFREL, and PPCRV.

The province’s removal from BARMM was meant to secure self-governance. Instead, it has left a vacuum—political, financial, and security-related. Unless new frameworks emerge to reintegrate Sulu meaningfully, either through a revised Bangsamoro structure or special autonomy provisions, the dream of sovereignty that animated its exit may prove hollow. Meanwhile, BARMM marches ahead without it—more unified, more funded, and, increasingly, more legitimate on the national and international stage.

Sulu has been left behind. Whether that leaves it freer or simply forgotten remains the question.

REFERENCES

Adlaw, J. (2025, June 11). MNLF wants Sulu back in BARMM. The Manila Times. https://www.manilatimes.net/

Comelec. (2025, June 14). Comelec: Plebiscite for Sulu reintegration not feasible this year. Philippine News Agency. https://www.pna.gov.ph/

Institute for Autonomy and Governance. (2025, May 5). Independent Election Monitoring Center Launched in Cotabato City to Safeguard BARMM and Sulu Elections. https://iag.org.ph/

Sarmiento, Bong S. (2025, June 3). BARMM bullish on blue economy with ADB’s $400-M funding support. MindaNews. https://mindanews.com/

Sarmiento, B. S. (2025, June 10). BARMM lawmakers fast‑tracking reapportioning of parliamentary district seats. MindaNews. https://mindanews.com/

Sarmiento, Bong S. (2025, June 11). Bangsamoro polls on October 13: Gun ban, campaign period set. MindaNews. https://mindanews.com/

Tamayo, B. (2025, June 17). BARMM election should push through. The Manila Times. https://www.manilatimes.net/

Unson, J. (2025, June 1). Lawmakers fixing adverse effects of Sulu’s separation from BARMM. The Philippine Star. https://www.philstar.com/

Unson, J. (2025, June 5). MNLF wants return of Sulu to BARMM’s territory. The Philippine Star. https://www.philstar.com/